Hidden lever for effective climate protection

Movement leads to friction. And friction causes energy to be lost — on a massive scale, as Oliver Koch calculates: “23 percent of the energy generated worldwide is lost through wear and friction in technical parts alone.1 Friction accounts for 20 per cent of these losses and wear for three per cent. In theory, we could shut down almost a quarter of the power stations if there were no friction or wear and tear.”

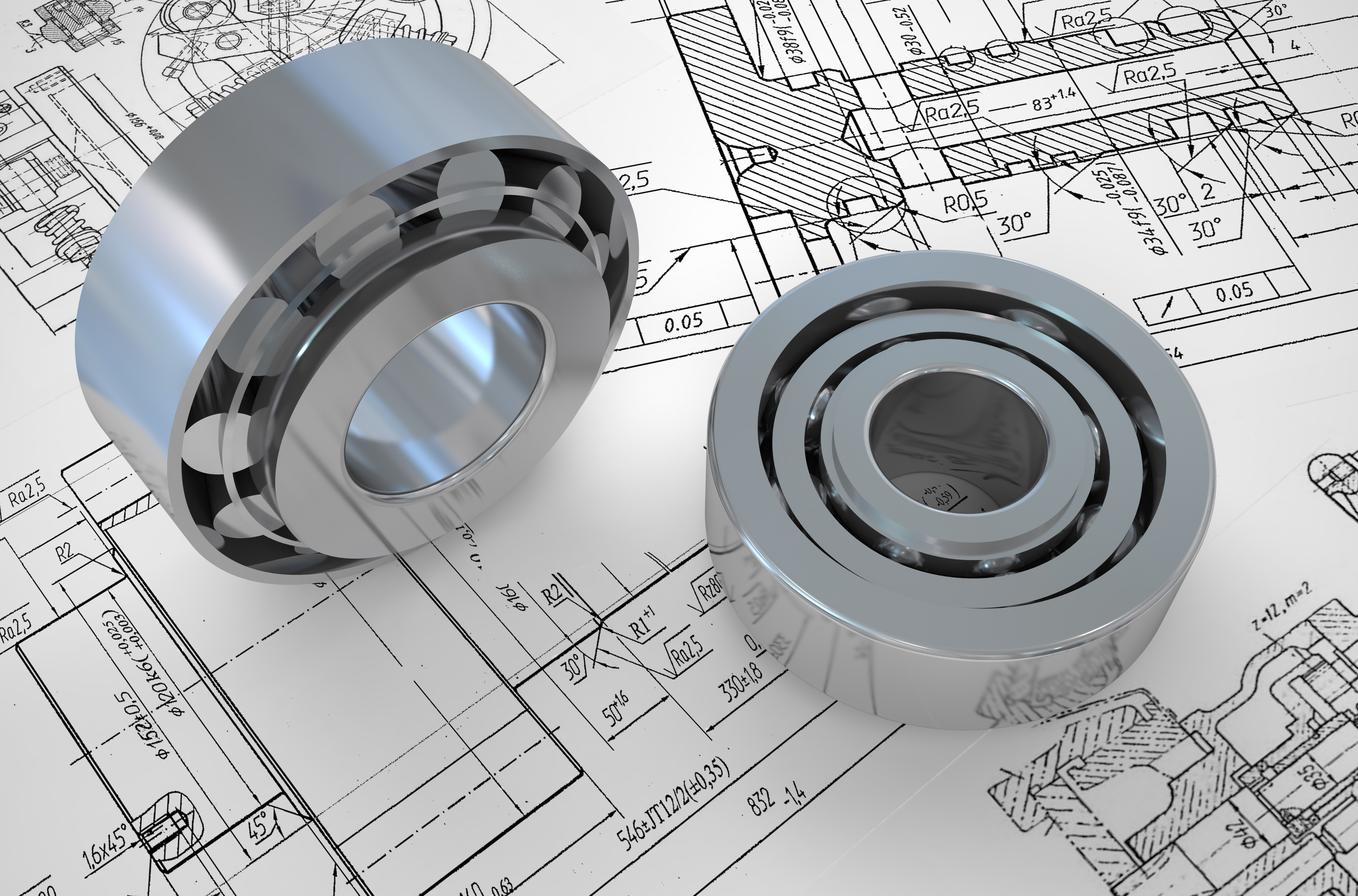

Koch's research team examines friction and wear from a sustainability perspective. The scientists see enormous potential in rolling bearings in particular. These components transmit motion via balls or rollers, ensuring that shafts, axles or swivel arms rotate or move in a controlled manner.

“There's a hell of a lot of movement in the world”

Modern rolling bearings with efficiencies of 99.9 per cent are already highly efficient. However, even a small amount of friction loss adds up to a significant amount on a global scale. “There's a lot of movement in our world,” says Koch.

The friction losses of the rolling bearings newly installed worldwide each year alone cause around 420 terawatt hours of energy consumption per year.2 Based on the German electricity mix, this equates to a global carbon footprint of around 182 million tons of CO₂ emissions per year. This equates to 0.5 percent of global CO₂ emissions, which is greater than the total emissions from all traffic in Germany. 'This is an underestimated lever for climate protection. If I reduce the losses in bearings used worldwide by ten percent, I save 0.05 percent of the global CO₂ budget. And that's without taking into account the fact that the average service life of a roller bearing is several years.”

Koch believes that the discussion in Germany underestimates the efficiency potential of such components. 'A speed limit would avoid around seven million tons of CO₂, and a ban on domestic flights around two million tons,' he says – significantly less than could be achieved with more efficient machine elements.

Simulations show the smallest changes

His research aims to improve efficiency by optimizing components so that as little energy as possible is lost. ‘We're not talking about a household drill that is used for ten minutes a year, but about systems with long operating times. This is because they generate ten to a hundred times more CO₂ during use than during manufacture,' explains Koch.

Because the remaining adjustment screws on already efficient parts are very fine, the researchers are using high-precision simulation models to search for improvement possibilities. Historically, mechanical engineering relied on trial and error, Koch explains: “You built things, tested them, and saw if they lasted longer or ran more efficiently.” Today, scientists digitally map technical systems to understand processes at the contact level — where metal meets metal, separated only by a very thin lubricating film, and friction occurs.

These simulations show how changes in material, lubrication or geometry affect energy losses. 'We have to look at the individual components and understand exactly what happens between the contact surfaces. Only then can we reduce friction and improve efficiency in subsequent steps,” says Koch.

Reducing friction often has a double effect

The researchers consider technical systems in all their complexity. This is because improving the efficiency of a bearing often has an impact elsewhere, ideally a positive one. Koch illustrates this with the example of a wheel bearing in an electric car. “In the case of the battery, the CO₂ footprint is mainly due to the complex manufacturing process. With wheel bearings, on the other hand, the CO₂ footprint is mainly generated during use. Reducing the power loss of a wheel bearing by just one watt not only saves CO₂ during use. The battery can also be designed to be smaller because less energy is needed to achieve the same range. This saves both in battery production and in charging losses.'

"Automatic" climate protection

Koch sees the appeal of such technical improvements in the fact that they take effect almost automatically once implemented. 'These are scalable solutions that work independently of the individual user,' explains Koch. 'When manufacturers design their products to produce less friction, this is built into every new device. This is climate protection that doesn't require anyone to give anything up consciously. It saves energy all by itself.'

However, there is a catch: while even minimal improvements are relevant for the global energy balance, they are often barely measurable for individual manufacturers. ‘Ultimately, everything depends on the economic analysis,’ says Koch. ‘The solutions we develop are created in close cooperation with industry and are designed for practical use. For example, as part of the Research Association for Drive Technology, we have developed a friction model that engineers can use to calculate and optimize systems. It is crucial that such developments remain cost-neutral so they can be widely adopted. Only then can they have an effect on climate protection."

1 Holmberg, K. and Erdemir, A. (2017), “Influence of Tribology on Global Energy Consumption, Costs and Emissions,” Friction, 5(3), pp 263–284.

2 Bakolas, V., Rödel, P., Pausch, M.: „Abschätzung der weltweiten Energiebilanz von Wälzlagern “, Tribologie + Schmierungstechnik 69 4, 41-47, 2022. DOI: 10.24053/TuS-2022-0022

LITERATURE FOR A DEEPER DIVE:

Bakolas, V., Rödel, P., Koch, O., Pausch, M. (2021). A first approximation of the global

energy consumption of all ball bearings. Tribology Transactions, 64(5), 883-890.

Wingertszahn, P., Koch, O., Maccioni, L., Concli, F., Sauer, B. (2023). Predicting Friction of Tapered Roller Bearings with Detailed Multi-Body Simulation Models. Lubricants, 11(9), 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants11090369

20 Minutes With Oliver Koch, June 2024. Website of the Society of Tribologists and Lubrication Engineers.

Diese Themen könnten dich auch interessieren: